Problems of Ecotourism

and Ecoresort Developments, Associated with the Restriction of Access of the Indigenous

Communities to the Vital Resources of Rural Regions in Developing Countries

Itam, Ekpenyong Bassey

Volgograd State

University of Architecture and Civil Engineering,

Ita, Ekpe Esien,

Dept. of Civil

Engineering, Cross River University of Technology, CRUTECH, Calabar, Nigeria.

Abstract

In the

earlier phases of ecotourism in the 1980-s, considerable emphasis was placed on

two major factors: tourists and pristine natural environments. This emphasis

can be discerned from the definition of ecotourism attributed to

Ceballos-Lascurain. Following deliberations of international conventions on

ecotourism, cultural and biological diversities (Berlin Declaration on

Biological Diversity and Sustainable Tourism of 1997; the Quebec Declaration on

Ecotourism of 2002; the Oslo Statement on Ecotourism of 2007 etc), another

significant factor has become recognized today – the indigenous communities, within

whose traditional domains ecotourism is expected to flourish. Research has

shown that the benefits that should accrue from ecotourism to indigenous

communities do not very often accrue, especially in the developing countries;

and this has resulted in conflicts between international tourists and

indigenous communities. In this paper, the possibilities of preventing such

conflicts, through the formulation of appropriate architectural conceptions for

ecoresort developments, have been explored.

Introduction – Ecotourism and the Developing Countries

According to G. Wall [20], the “term

‘ecotourism’ is usually attributed to Ceballos-Lascurain, who defined it

as ‘tourism that consists in travelling to relatively undisturbed or uncontaminated

natural areas with the specific objective of studying, admiring, and enjoying

the scenery and its wild plants and animals, as well as any existing cultural

manifestations (both past and present) found in these areas.’” In this early

definition of ecotourism, the emphasis on the pleasure of the tourists is

evident. This emphasis is still being played out by investors in ecotourism projects,

in circumstances in which appropriate national regulations are not strictly

enforced (the developing countries). This contradicts the present worldview of

ecotourism (Berlin Declaration on Biological Diversity and Sustainable Tourism

of 1997 [3]; the Quebec Declaration on Ecotourism of 2002 [19]; the Oslo

Statement on Ecotourism

According

to H. Ayala [1, 2], natural and cultural heritages that were previously considered

as peripheral or background issues in mass tourism, have now been “re-labeled”

as the foremost attractions in ecotourism; and this has drawn the rural regions

of the developing countries into the center stage of the orbit of world tourism.

L Mastny [12] has described these trends in the following manner: “Rushing to

capitalize on their rich natural and cultural attractions, many developing

countries welcome tourism as a way to stimulate investments, generate foreign

exchange earnings, and diversify economies. Tourism can be more lucrative and

less resource-intensive than growing a single cash crop or pursuing traditional

industries like mining, oil development and manufacturing”. According to Mbaiwa

and Stronza [13], sustainable tourism has great potential “to bring social,

economic and environmental benefits” to developing countries [1, 2, 12, 13].

The

significant shift in international tourism that has accompanied the rise of

ecotourism has been noted. The percentage of international tourists that traveled

to the developing countries rose from about 7.7 percent (in the 1970-s) to

slightly above 20 percent (by the end of the 20th century) [12].

This trend has continued to intensify within the first decade of the 21st

century. According to the 2008 report of WTTC (World Travel and Tourism

Council) [23] the growth rate of international tourism in Africa (5.9%),

Pacific region of Asia (5.7%) and Middle East (5.2%) have superseded the value

4%, the global average annual growth rate since 2004; while the growth rates in

America (2.1%) and Europe (2.3%) fell below the average. The contribution of

travel and tourism to economies and employment worldwide is expected to rise

from 8.4% (in 2008) to 9.2% (by 2018). Thus the influx of international

tourists into the rural regions of the developing countries will continue to

increase; and the developing countries will continue to welcome these trends towards

the improvement of their national economies [12, 23].

Ecotourism

is associated with some levels of responsibility. The expectation is that the

social and economic benefits that accrue to developing countries from

ecotourism must result in the improvement of the livelihoods of the indigenous

communities and also foster the cause of conservation; and this position has

been emphasized in the work of P. Wight [22]: “Ecotourism: Ethics or

Eco-Sell?”. Thus, resort developments for ecotourism (ecoresort developments)

must be based on this fundamental criterion of ecotourism – the recognition of

the rights of indigenous communities to resources located within their

traditional domains. However, recent studies have revealed that the planning of

ecotourism and ecoresort developments in developing countries has not often been

sufficiently comprehensive; very often, neglecting the interests of indigenous

communities. Some of the trends and consequences of this negligence are

discussed in this paper [22].

Ecotourism and the Vital Interests of the Indigenous

Communities

According

to H. Ayala [1, 2], the incorporation of the indigenous communities in ecotourism

and ecoresort development programmes is of critical importance to the success

of the ecotourism programme itself. The indigenous people possess very adept

knowledge of the natural and cultural heritages located within their traditional

domains. This adept knowledge gives them immense capacities to contribute to

the prosperity of an ecotourism programme that offers them very tangible

benefits; and also to destroy one that is not directly beneficial to them. According

to J. Butcher [5], the indigenous communities must constitute a very distinct

and fundamental factor in the planning, operation and regulation of ecotourism

and ecoresort development programmes [1, 2, 5].

The Final

Report of the World Ecotourism Summit, 2002 [18] posited that ecotourism should

be the means by which indigenous communities “conserve and derive benefits from

natural and cultural resources” located within their traditional domains [18]; and

that, as a “principle”, ecotourism and ecoresort development programmes should

“allow indigenous communities, in a transparent way, to define and regulate the

use of their areas at the local level” [18]. Furthermore, they should provide

“a source of livelihood for local people which encourages and empowers them to preserve

the biodiversity in their area” [18]. The Quebec Declaration on Ecotourism [19]

argues for the promotion of “the cultural integrity of the host community”; and

furthermore:

Recognize

the cultural diversity associated with many natural areas, particularly because

of the historical presence of local and indigenous communities, of which some

have maintained their traditional knowledge, uses and practices, many of which

have proven sustainable over centuries.

UNEP and

UNWTO, 2002b

The alienation

of indigenous communities from the social and economic benefits of ecotourism (by

curtailing their access to the vital resources located on their traditional and

historical domains) is thus an aberration of the cardinal principles of ecotourism

and ecoresort developments; but it has often been observed in the processes of

development of tourism facilities that are undertaken with off-shore capital (most

especially in the developing world) [18, 19].

P. Pattullo [14] and A. Holden [10]

have cited the example of Antigua, where long stretches of local beaches have

been destroyed by companies engaged in the construction of tourism projects

locally, and also in the Virgin Islands. A. Holden [10] has discussed the case

of Goa (in India), where the development of tourism hotels has excluded the

local population from the use of their beaches; at ‘Cidade de Goa Hotel’, a

tourist hotel in Goa, a 2.4 meter wall fence was constructed, demarcating the

beach and thereby curtailing the access of the local peoples to it [10, 14].

Restriction

of access of the local peoples to water and electricity has also caused discontent

in Goa. At the ‘Taj Holiday Village’ and ‘Fort Aguada Beach Resort Hotels (in

Goa), tourists have unlimited access to water, while the nearby villages are

denied access to water (from the pipeline) even for up to one or two hours in a

day [10]. In Goa also, the local peoples lack dependable access to electric

power; yet one guest (in a 5-star tourist hotel in the area) consumes 28 times

the electric power used by one local resident [10]. These restrictions have

resulted in protests against tourism (and sometimes open aggression against

tourists) in this region [10].

N. Salem [15]

has estimated that the quantity of water consumed by 100 guests in a luxury

tourist hotel in 55 days is sufficient to sustain the households of 100 rural

farmers for three years, and 100 urban families for two years. A. Holden [10]

has cited the case of Tepotzian (in Mexico), where the local people protested

against the development of 800 tourist villas along with a golf course. It was

estimated that the water requirements for daily sustenance of the project,

would result in drastic water shortages in the town. Other problems (of tourism

and resort developments) associated with the curtailment of the access of

indigenous people to water resources have also been documented. One instance

involves the diversion of water upstream for the development of resorts and

other tourist facilities; resulting in the lack of sufficient water for the

irrigation of the farmlands in the indigenous communities. Another instance

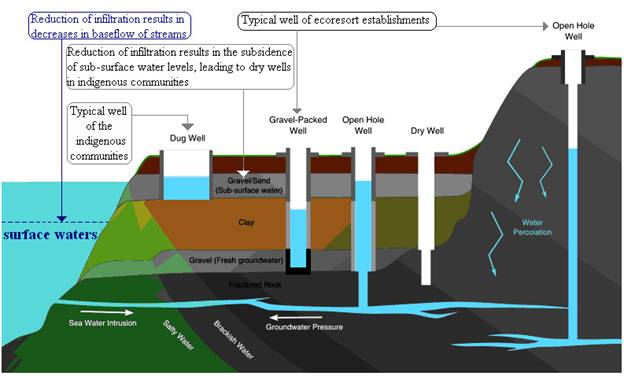

involves the over-extraction of sub-soil waters through the deep wells located

in resorts, leading to the lowering of sub-soil water levels; and, in

consequence, the shallow wells located in the indigenous communities become dry

(see Fig. 2) [10, 15].

Another

key issue is access of the indigenous communities to land for their livelihood

activities; agriculture and grazing lands, in particular. Large expanses of

farmlands are used up for the development of tourism facilities (airports, golf

courses, resorts etc). The use of agricultural lands for the development of

tourism facilities (seaports and airports) has resulted in heavy dependence on

imported foods in the Maltese Islands [4, 10]. In Kenya, the establishment of

the Masai-Mara Game Park has resulted in the displacement of the Masai people

form their traditional grazing fields and lands. L. Mastny [12] has discussed

the specific problems of golf in resort developments. Golf demands land; and

every year “up to 5,000 hectares of the Earth’s land surface – an area half the

size of Paris – are cleared for golf courses” [12]. It also demands water; “one

18-hole course can consume 2.3 million liters of water daily” [12]. The

specific case of an island in Malaysia has been cited, where a popular golf

course consumes “as much water annually as a local village of 20,000” [12].

Thus, it is not advisable to associate golf with ecoresort developments in the

rural regions of the developing countries [4, 5, 12].

In

general, tourist demands for specific locations change very rapidly. In the

events of such changes, the use of prime agricultural and grazing lands for

tourism development may result in serious ecological and economic consequences

for the indigenous peoples; and this would be a contradiction of the cardinal

principles of ecotourism and ecoresort developments, as articulated by the UN [18,

19].

Ecoresort Developments for Developing Countries

The ecoresort

is the principal factor that places international tourists directly within the traditional

domains of the indigenous peoples; and creates demands for resources that are

often in very short supply in the rural regions of the developing countries:

water, electricity and appropriate sewage disposal systems. In the process of

its development, care must be taken to avoid the use of prime agricultural and

grazing lands, upon which the livelihoods of indigenous peoples have depended

for several generations. C. W. Shanklin [16] has recommended that comprehensive

studies and researches on the vital resources of the region should constitute

the prerequisites for ecotourism and ecoresort developments in ecologically

sensitive territories. The objective is to ensure that indigenous peoples have

equitable access to the same resources upon which they depend for their

livelihood activities; and upon which tourism development also depends. In

order to reduce the ecological impacts of ecotourism on indigenous communities,

ecoresort development programmes should be based on detailed studies,

pertaining to the following issues:

·

the physical structures and peculiarities of the territory, and

also traditional landuse patterns of the indigenous communities;

·

the locations of the indigenous communities in the territory, and the

peculiarities of their settlement patterns;

·

the hydrographic and hydrological peculiarities of the territory;

·

the general characteristics of the vital resources of the

territory, which will be placed in the common usage of the tourists and the

indigenous communities;

·

the long-term relationships of the ecoresort establishments and

the indigenous communities.

This study

has revealed that, lured by the high revenues that accrue from tourism, national

governments (in developing countries) have often granted inappropriate

concessions to foreign tourism development organizations; to the detriment of

the socio-economic interests of the indigenous communities. Thus, driven by

poverty and desperation, the indigenous communities could resort to destroying

the natural and cultural resources upon which tourism development relies; and

the inevitable decline of tourism itself would set in [1, 2, 16, 18].

Discussion – The Ecoresort Establishment and the Indigenous

Peoples

In

specific case of Cross River State of Nigeria, the Cross River National Park

complex and the large expanses of tropical rainforests that surround it

constitute the principal resources for ecotourism and ecoresort developments. A

very large portion of the forest estates outside the national park complex is

constituted as community forest estates. The only condition for ecotourism and

ecoresort development programmes to be successful here is if they would be

beneficial to the indigenous communities. There are already existing interest

groups that are poised at luring the local peoples into poaching and illegal trade

in good quality timber; and NGO’s have been combating these activities (by

local court actions and international campaigns) for about two decades now. The

indigenous peoples would thus have the incentives to apply their in-depth

knowledge of these natural resources towards the destruction of an ecotourism

that would not grant them very tangible benefits.

Architecture of the Ecoresort Establishment. In the architecture of

ecoresorts, the fundamental aspiration is to create an ecoresort environment

that is both ecologically and culturally compatible with its location (the concepts

of ecological sensitivity, and also of ecological and cultural affinity).

According to R. K. Dowling [9], an ecoresort should be

“environmentally sensitive” in design; the design, development and management

of an ecoresort should be based on the principle of minimization of “its

adverse impact on the environment, particularly in the areas

of energy and waste management, water conservation

and purchasing”. Waste management deserves

appropriate attention in the architecture of ecoresorts developments in rural

regions; according to L. Mastny[12], the “UN Environment Programme (UNEP)

estimates that the average tourist produces one kilogram of solid waste and

litter each day” [1, 2, 9, 12].

The

ecoresort has a symbolic presence in the rural region in which the business of

ecotourism is conducted; within the consciousness of the indigenous peoples it

is the physical embodiment and reflection of ecotourism. It is essential to use

the architecture of ecoresorts as a means of invoking positive impressions of

ecotourism on the part of the indigenous peoples. The impression created by the

physical manifestation of the ecoresort could be a feeling of deprivation and

oppression; if the presence of the ecoresort results in the deprivation of the

access of the indigenous peoples to the vital resources, on which their lives

have depended for several generations. On the other hand, the indigenous

peoples would be positively disposed towards ecotourism if, through it, their

youths have meaningful employment and also if the state of environmental

services in the region are improved; for example, introduction of: 1) new

methods of electric power supply (by solar energy); 2) new water schemes that

are also made available to the indigenous communities. The long-term benefits

that the ecotourism venture would derive from such gestures far out-weigh the

initial cost outlays.

The application

of the principle of cultural affinity or contextualism in the architecture of

ecoresorts is very essential in rural regions. According to H. Ayala [1, 2],

cultural affinity means much deeper than the cosmetic application of local

traditional motifs and artworks within an ecoresort complex; it means

association with the local cultures by the incorporation of elements of the

traditional architecture and arts of the local peoples in ecoresort developments.

An ecoresort that is culturally associative with the region is most likely to

invoke the required positive attitudes on the parts of the indigenous

communities. In order to achieve this, it is essential to apply local

architectural styles, crafts, technologies and building materials. In the

planning of the ecoresort settlement, it is also essential to create special

spaces for social and cultural interactions between the indigenous communities

and the tourists. In the contrary circumstance, an ecoresort that is based on

foreign architectural styles manifests as a foreign imposition on the

traditional domains of the indigenous peoples; and the attitudes of the local

peoples would be shaped by their perceptions of such foreign intrusion. From

the perspective of the international tourists, it would be more rewarding and desirable

to study a culture by living within its characteristic spatial configurations,

than by viewing it in films, picture galleries and museums [1, 2].

Road Engineering Infrastructures. It would ordinarily

be presumed that construction of road infrastructures for ecoresort

developments in the rural regions of the developing countries would only result

in direct benefits to the indigenous peoples. Within this general conception, in

opening up the rural regions to international tourism, such road transportation

infrastructures are expected to grant the indigenous people improved

transportation networks for the conduct of their livelihood activities. This is

unarguably true; however recent studies have also shown that unless such road

engineering infrastructures conform to specific environmental standards, they

could also become the direct sources of some ecological problems in the rural

communities. The principal problems that could be associated with road

infrastructures are distortion of natural hydrological processes and pollution

of water resources, by reason of the use of impervious pavements. The

probabilities are that many roads would be constructed with impervious pavements;

because, in comparison, permeable pavers are fairly scarce in developing countries,

and they are also two or three times more expensive [6, 7, 8].

Ecoresort

buildings and complexes are usually small; and empirical studies have indicated

that the cumulative surface areas of the roads that lead tourists to the

national parks and to the ecoresort establishments as well as the walkways

within the ecoresort could account for above 65-70 percent of imperviousness of

the territory. Thus it is expedient to address the subject of ecological

impacts of imperviousness from the point of view of design of road engineering

infrastructures.

Recent

studies have shown that the use of impervious pavements in the construction of

roads has serious environmental impacts on the water resources and aquatic

ecosystems. In the specific context of ecotourism developments in the rural

regions of sub-Saharan Africa, depletion or pollution of water resources

amounts to the curtailment of the access of the indigenous peoples to the vital

resources upon which their lives had depended for generations. The principal

ecological impacts of impervious pavements on the water resources of the

indigenous communities are: 1) increases in the volumes of runoff; 2) increases

in peak discharge rates; 3) increases in bankfull flow; and 4) decreases in

baseflow [8].

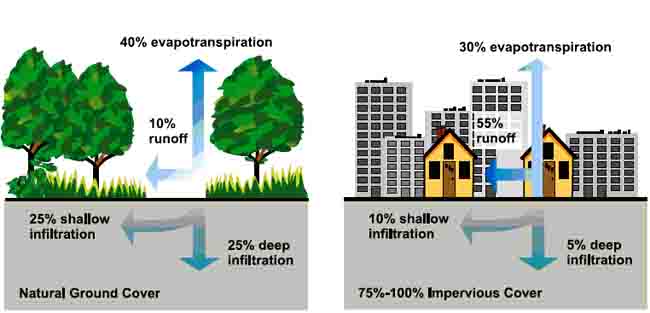

The use of

impervious pavers and concrete drains in road construction results in decreases

in infiltration and increases in stormwater runoffs (see fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Reduction in infiltration by reason of increases in

imperviousness results in the depletion of underground waters and pollution of

surface waters; and thereby could lead to the curtailment of the access of indigenous

communities to fresh water in ecotourism development. Credit for

diagramme is ascribed to: Wikimedia Commons.

Runoff

coefficient is the numerical factor (ranging from 0 to 1) that expresses the

volume of runoff in relationship with a given volume of rainfall. Studies on

the relationship between imperviousness (measured in percentages) and runoff

coefficient have shown that there is a direct relationship between these two

parameters; runoff coefficient approaches 1 as imperviousness approaches 100

percent [7]. Increases in runoffs lead to the discharge of large volumes of

water into surface waters at periods of peak rainfalls; this is the phenomenon

that is described in this work as “increases in peak discharge rates”. Stormwater

runoffs contain pollutants that could render surface waters unsuitable for

domestic use. Increases in runoffs thus result in increased pollution of water

resources; and also in higher risks of floods in communities located on the

sides of streams, lakes or rivers. Bankfull flow is the condition in which the

channel of a stream (or other surface waters) is filled to the brim; the point

at which further addition of water from stormwater runoffs results in the

overflow of surface waters on to the flood plains in the communities. The

frequency of the occurrence of this overflow is related to the volumes of

stormwater runoffs that reach the stream [6, 7, 8].

Increases

in stormwater runoffs are indicative of reduction in infiltration (see Fig. 1).

Reduction of infiltration affects the water resources of indigenous communities

in two ways. Firstly, it results in decreases in baseflow. Baseflow is the

discharge from underground waters that supports the flow of streams during the

dry seasons. Reduction of infiltration reduces the capacities of underground

waters to support the flow of streams in dry seasons and this could result in

dry streams during such seasons. Secondly, the depletion of underground waters

could result in the problem of dry wells in the communities; because the

communities depend on shallow wells for their supply of drinking water. In

ecoresort developments, the problem of dry wells could also occur in accompaniment

with the circumstances of over extraction of underground waters for use in

tourist establishments. In such instances, the shallow wells of the communities

run dry, while the deep wells in the tourist establishments continue to

function (see Fig. 2) [6, 7, 8].

Fig. 2. Problems of imperviousness, increased runoffs and the water

resources of indigenous communities in ecoresort developments. (Illustration is done by the authors by the adaptation and

modification of the original base drawings obtained from Wikimedia Commons). Credit for base drawing is ascribed to:

Wikimedia Commons.

In the circumstances

in which it is inevitable to use impervious pavements, it becomes desirable to

apply ecological methods towards the reduction of the total volumes of runoffs

that are discharged into surface waters. This requires the application of the

modern technique of “source control”, an approach radically different from the

20th century approach, which consisted in the collection of

stormwaters from the sources and the transportation by concrete drain channels

into nearby surface waters. Source control involves the collection of

stormwaters from impervious pavements into systems that facilitate their

infiltration, in such manners that no volume of stormwaters reaches the surface

waters. In the construction of roads and walkways, the use of concrete drain

channels should, therefore, be completely avoided. Roads and walkways should be

constructed in the form of an integrated system in which the runoffs are

directed into vegetated drains that are constructed alongside the roads and

walkways. Vegetated drains facilitate the infiltration of stormwaters into the

subsoil. At the points at which the capacities of the vegetated drains (for

total infiltration of the runoffs) have been exceeded, then the stormwaters in

the vegetated drains should be directed into retention basins and/or

constructed wetlands. The objective is to ensure the complete collection and

infiltration of the total volumes of stormwaters generated by impervious

pavements [6, 7, 8].

Conclusion

In the specific

instance of ecotourism and ecoresort developments in

·

The

ecoresort development programme should begin with comprehensive studies of the

natural and cultural resources of the territory, to reveal the intrinsic values

of these resources to the indigenous communities.

·

Comprehensive

studies should also be conducted on the spatial structures of traditional

settlements of the indigenous communities, their traditional land-use patterns

and livelihood activities; and also their access to the vital resources of the

territory (such as water and electric power).

·

Incorporation

of the members of the indigenous communities into the decision-making processes

in the ecoresort development programmes would be desirable and consistent with

the demands of the UN.

·

The

architecture of ecoresort buildings should incorporate traditional

architectural styles; and also, local materials and technologies should be

applied in the construction and maintenance of buildings and complexes.

·

It

is essential to provide cultural parks and other places for social and cultural

interactions, in order to enable international tourists to properly appreciate

the cultural peculiarities of the region.

·

Pervious

pavements are recommended for roads and walkways. In the events that the use of

impervious pavements should be inevitable, then the runoffs from roads and walkways

should be directed into vegetated drains and infiltration trenches or basins,

in order to eliminate the possibilities of discharge of stormwater runoffs into

surface waters.

References

1. Ayala, H. (1996).

Resort Ecotourism: A Paradigm for the 21st Century. Cornell Hotel

and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 1996; Vol. 37: pp 46-53.

2. Ayala, H. (1998).

3.

4. Briguglio, L.

and Briguglio, M. (1996). Sustainable Tourism in the Maltese Isles. In

Briguglio, L.,

5. Butcher, J. (2006). The United

Nations International Year of Ecotourism: a critical analysis of development

implications. Progress in Development Studies 2006; Vol. 6: pp 146-156.

6. Cahill, T. (2000).

A Second Look at Porous Pavement/Underground Recharge. Technical Note #21 from

Watershed Protection Techniques. In Schueler, T. and

7. CWP (2000). The

Importance of Imperviousness. Article 1; Watershed Protection Techniques. In

Schueler, T. and

8. CWP (2003). Impacts

of Impervious Cover on Aquatic Systems. © Center for Watershed Protection.

9. Dowling,

R. K (2000). In Jafari,

J. (editor). Encyclopedia of tourism. Routledge,

10. Holden,

A. (2003). Environment and Tourism.

11. Honey, M

(2008). Ecotourism and Sustainable Development: Who Owns

12. Mastny, L. (2001). Traveling

Light: New Paths for International Tourism. Worldwatch Paper 159; © Worldwatch

Institute 2001.

13. Mbaiwa, J. E. and Stronza, A. L.

(2009). The Challenges and Prospects of Sustainable Tourism and Ecotourism in

Developing Countries. The SAGE Handbook of Tourism Studies. SAGE Publications,

2009. Accessed: 1 May. 2010. http://www.sage-ereference.com/hdbk_tourism/Article_n19.html.

14. Pattullo,

P. (1996). Last Resorts: the Cost of Tourism in the

15.

16. Shanklin,

C. W. (1993). Ecological Age: Implications for the Hospitality and Tourism

Industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, Vol. 17: pp 219-229.

17. TIES (2007).

18. UNEP and UNWTO (2002a). The World

Ecotourism Summit – Final Report. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

and United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) 2002.

19. UNEP and UNWTO (2002b). The

20. Wall, G. (2000). In Jafari, J. (editor). Encyclopedia

of tourism. Routledge,

21. Weaver, D. (2001). Ecotourism.

John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd., Sydney and

22. Wight, P. (1993).

Ecotourism: Ethics or Eco-Sell? Journal of Travel Research 1993; Vol. 31

(Winter): pp 3-9.

23. WTTC (2008).

Progress and Priorities 2008/09. © 2008 World Travel and Tourism Council, www.wttc.org.

Ïîñòóïèëà â ðåäàêöèþ 23.08.2010 ã.